Hawk House

Hawk House was a small but influential design venture that helped define the California Modern lifestyle. Founded by Edwin “Stan” Stanton Hawk Jr. and his wife, Ethyle O. Hawk, the company grew from ideas first tested in their 1939 Harwell Hamilton Harris–designed home in Silver Lake. Through collaborations with landscape architect Roberto Coelho Cardozo, Hawk House produced a line of inventive indoor-outdoor furnishings that became fixtures in Case Study Houses, and were embraced by leading designers, retailers, and museums. Though modest in scale and short-lived, Hawk House left an enduring imprint on the visual and material language of postwar California design.

Edwin “Stan” Stanton Hawk Jr (1904-1958) was born in Los Angeles, the youngest of four children of Edwin Stanton Hawk Sr. and Julia Spang Bruff Hawk. Stan Jr. married Ethyle O. Miller in October 1935. He worked as a salesman at B & A Radio and Tire Company and she had a position at an insurance company.

Stan and Ethyle commissioned Harwell Hamilton Harris to design a house for them on Silver Ridge Ave in Silver Lake, Los Angeles. It was completed in 1939 and it would be where they would operate their company, Hawk House.

In 1947 Stan collaborated with his wife Ethyle and Landscape Architect Roberto Coelho-Cordoza on designs for Hawk House products. One article alludes to the concepts initially being developed for the Hawks own home and garden. The name “Hawk House” was copyrighted in 1948, the same year production began.

Hawk House (1939) by Harwell Hamilton Harris

2421 Silver Ridge Ave, Los Angeles. Read more about the house, here.

Roberto Coelho Cardozo (1923-2013) was of Portuguese descent and born in Santa Cruz, Californian. He studied Landscape Architecture at the University of California (Berkeley) from 1943-1947. After receiving his degree, he worked with Garrett Eckbo and three of the projects they collaborated on are featured in Eckbo’s landmark book, Landscape for Living (1950). In 1952 Roberto moved to Brazil and he began teaching at the University of São Paulo. He became a prominent figure in modern landscape design there and is credited with incorporating Landscape Architecture into the University’s architecture program. Along with influencing generations of architects at the University with ideas of California modernism, he worked on projects with many of the country’s top architects.

Image: Roberto Coelho-Cordoza and Burle Marx (1952) via Arquivo Arq

The Hawk House Line

Hawk House offerings included several variations of barbeque-braziers, ashtrays and hurricane lamps (powered by either candles or wired for electricity). Some of the models are seen here on the deck of the Hawk’s home.

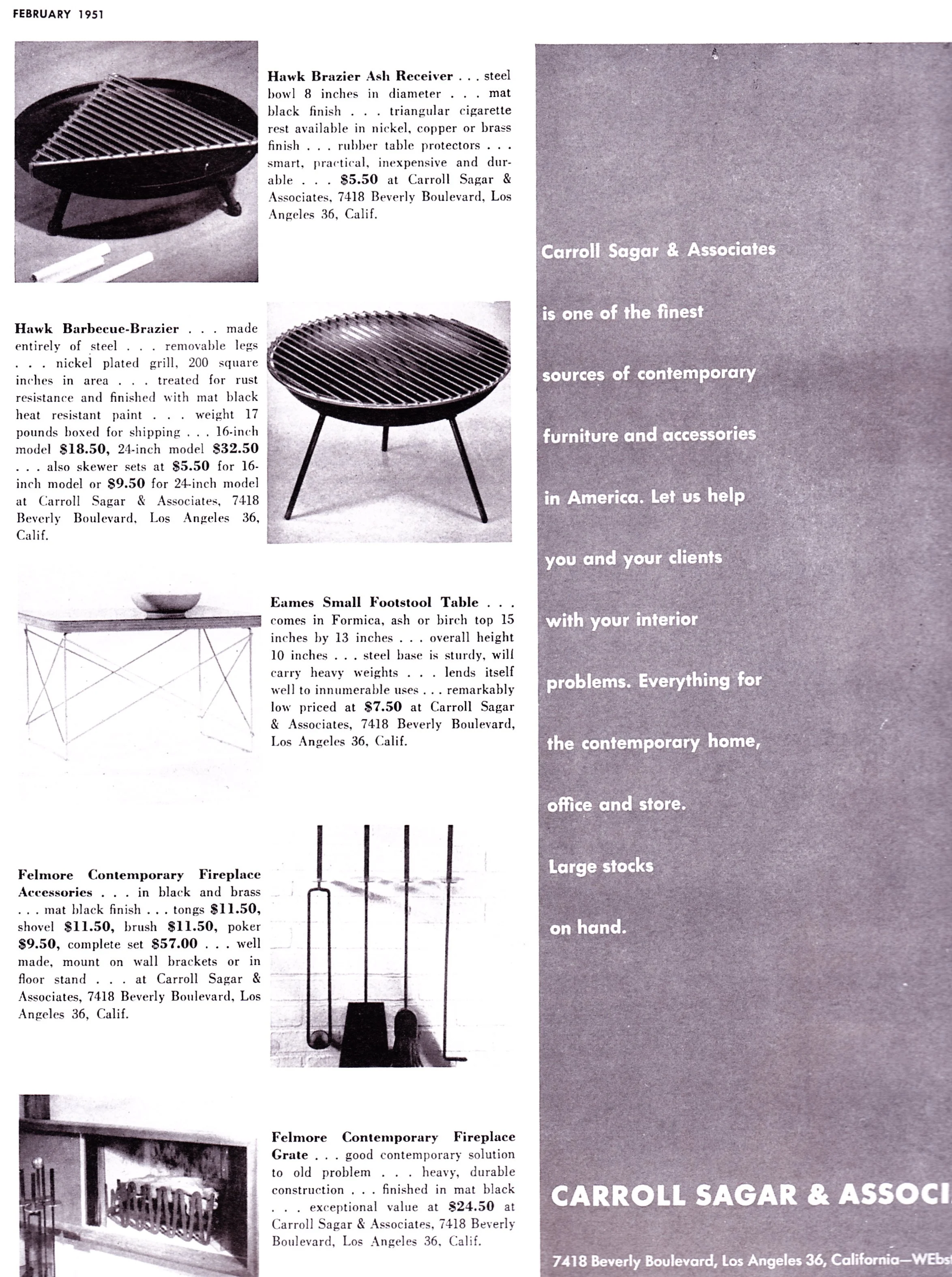

The braziers were constructed with readily available steel fuel tank end caps modified with three legs in various forms. They were produced in 16", 24" & 36" models with nickel plated grills. Some braziers were also made with spun copper sitting on a steel tubular ring base.

There were also instances where the pieces were fabricated for specific projects, such as the William Alexander House from 1953.

Hawk House products were “Merit Specified” for all Arts & Architecture Magazine Case Study Houses beginning in 1948. They appeared in-situ throughout the interiors and exteriors of many architect-designed homes of the era, becoming part of the visual and material language that defined mid-century California architecture.

These installations were frequently captured by architectural photographer Julius Shulman. In Shulman’s photographs, Hawk House products often functioned as subtle components of the composition, integration with landscape, and emphasis on outdoor living. Hawk House became closely associated with the “outside-in” California Modern ethos that blurred the boundaries between interior and exterior spaces.

In 1950, the Hawk House barbeque-brazier received national recognition when it was featured in the Walker Art Center’s Everyday Art Quarterly, a publication devoted to highlighting exemplary modern design for daily living. That same year, the brazier was selected for inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition house designed by Gregory Ain. Its placement within the MoMA house underscored the brazier’s role as both a functional tool and a refined expression of postwar design values.

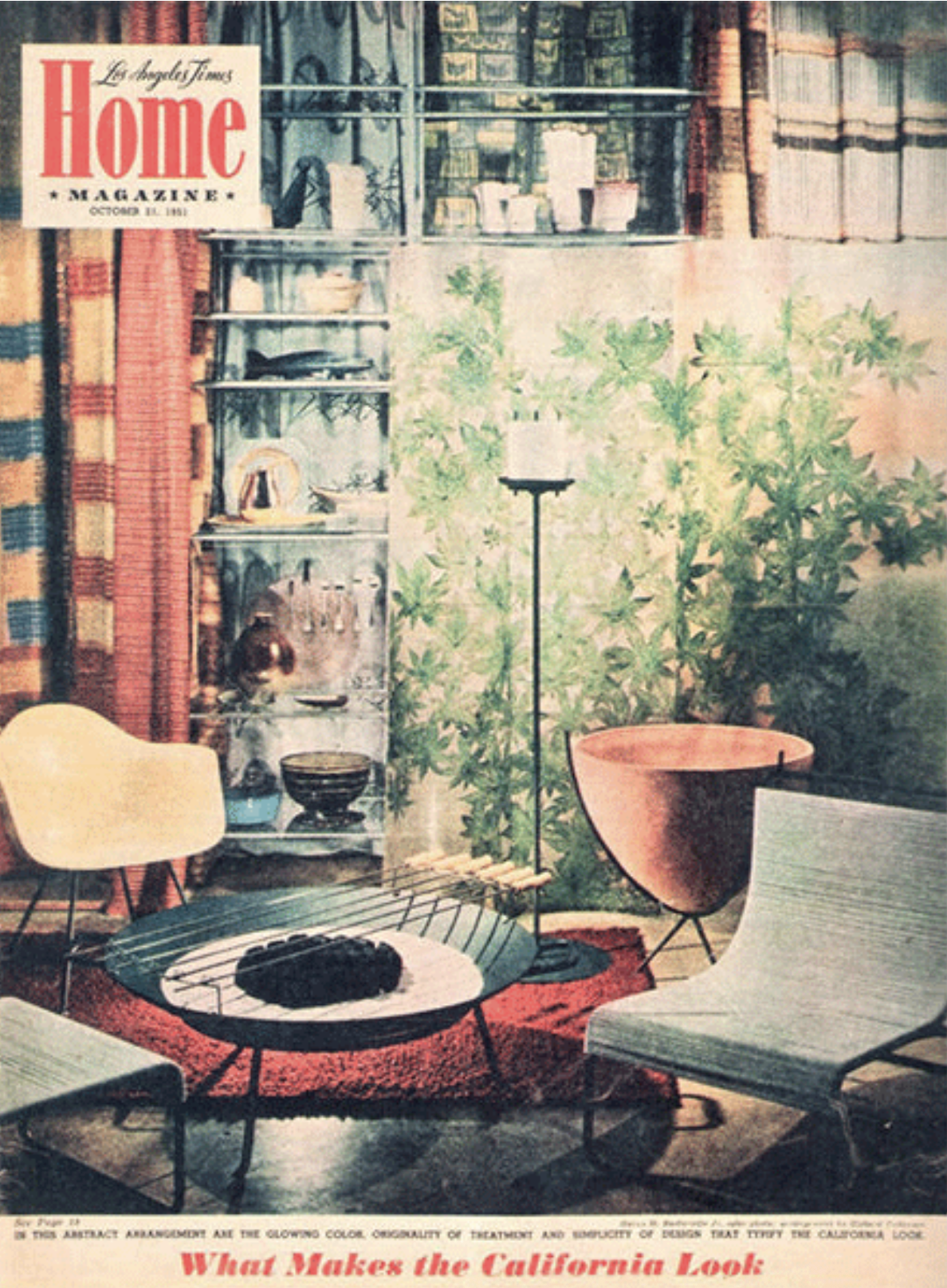

The California Look

The following year, in 1951, both the brazier and a Hawk House hurricane garden lamp were prominently displayed on the cover story of the Los Angeles Times Home magazine, titled “What Makes the California Look.” Shown alongside iconic works by Van Keppel & Green, Charles and Ray Eames, and Architectural Pottery, the pieces were presented as essential elements of the emerging California Modern lifestyle. Beyond these, Hawk House products continued to appear throughout leading national design publications, including Interiors, Better Homes & Gardens, and Sunset.

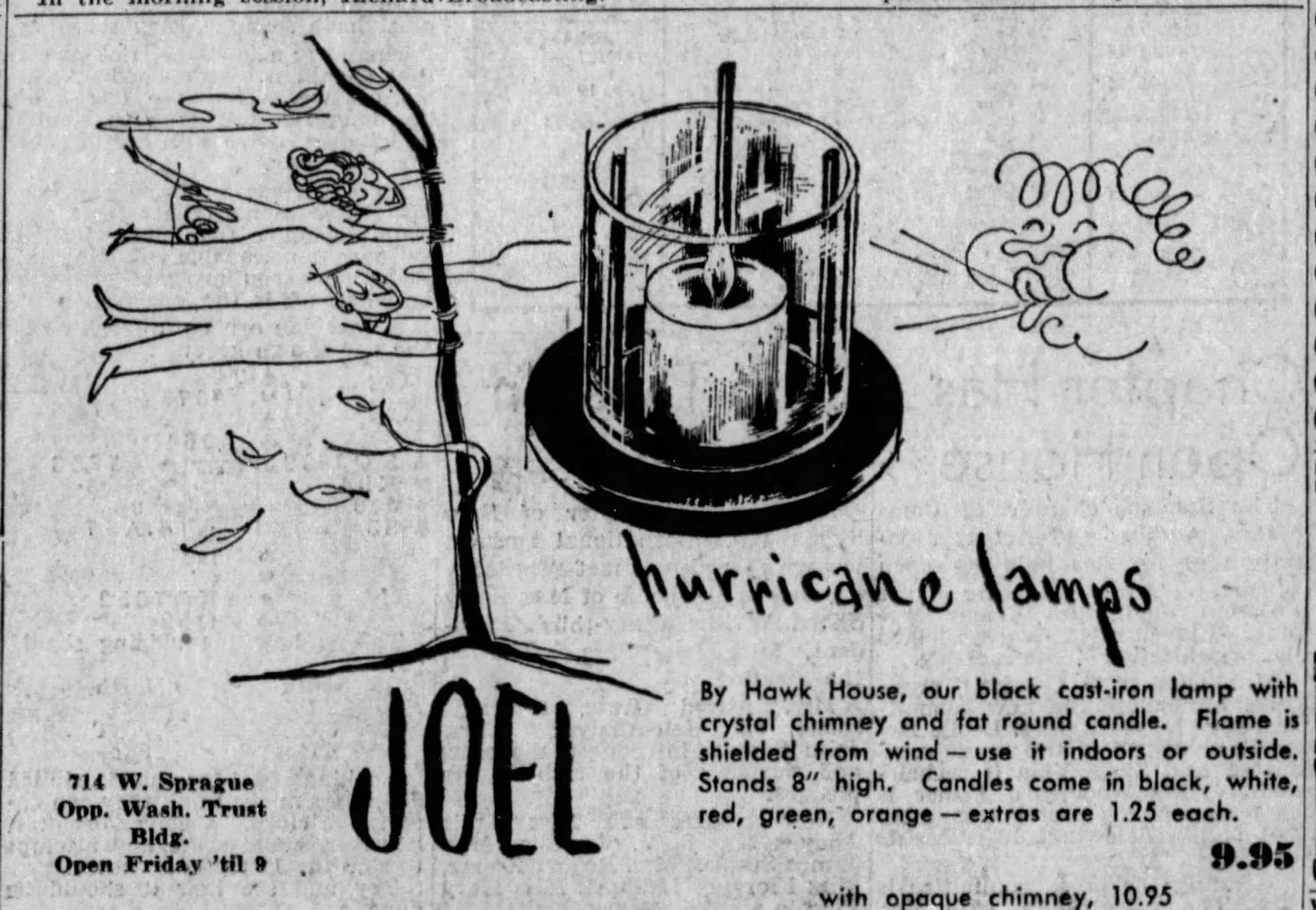

In addition to exposure from museums and design-related publications, some of the top retailers in California, such as Carroll Sagar & Associates, Frank Bros, Van Kepple-Green, Barker Bros and Pacific Shop sold the Hawk line. They were also distributed nationally at Trend (Lincoln), Carson Pirie Scott (Chicago), Joel (Spokane), and Boysen (Honolulu). A pair of electrified hurricane lamps even made a cameo on George Nelson bedside tables in a 1950’s Herman Miller catalog photo.

Hawk House custom spun copper bowl with iron tripod base Brazier for a house by architect William Alexander that was published in Arts & Architecture magazine in 1954. The copper hood was made by Prizant sheet metal.

Photo: Julius Shulman 1953 © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute

By the mid-1950s Hawk House was no longer being advertised in magazines, including the long running ads in Arts & Architecture magazine. Around that time, many smaller boutique manufactures like Hawk House were going out of business. The furniture industry was moving towards large corporations who could mass produce items more efficiently (with some copying designs) and sell them at cheaper prices.

Stan passed away in 1958, at the age of 53. Ethyle sold the Hawk House property in 1960.